Web-site restrictions

ACAT will be moving to a new web site on Thursday, 10th April.

In preparation, from Friday, 4th April this old web site will not let members renew their membership, and any other changes members make, e.g. their personal details, will get ‘lost in the move’.

Urgent membership renewals should instead be done by contacting Alison Marfell.

Compassion in CAT

Wilde McCormick, E., 2011. Compassion in CAT. Reformulation, Winter, pp.32-38.

Introduction

The word “compassion” now accompanies approaches to psychotherapeutic work such as Compassion Focussed Therapy (formerly known as Compassionate Mind Training) developed by Paul Gilbert and his team. I have been interested in compassion as an extension of mindfulness for many years, but the concept of, and depth of, meaning invited by “compassion” is not straightforward - it embraces many complex factors and ideas.

This article has grown out of my contribution to the ACAT Hatfield conference of 2009 called Keeping Healthy Hearts and Minds in CAT. I was asked to speak on ‘Compassion in CAT’. This contribution stimulated some interesting dialogues and awakened a further curiosity in me. I found that, when faced with an audience of over a hundred people, I was unable to present details of my actual work with patients, showing their diagrams, even though I had prepared them. The feedback responses seemed polarised - about half reported boredom and cutting off, wondering about relevance, with the other half experiencing warmth and engagement. I continue a dialogue with many people from different backgrounds, and within CAT, about several issues: what does compassion look like within the therapeutic relationship? What helps compassion to be present, to grow between two people; and if it is a ‘good thing’, why?

Preparation

Fundamental qualities of a therapist include deep listening, curiosity, and openness. In CAT we also are aware of our own diagrams and what we bring of ourselves to the encounter with another. Whilst reading this article, I invite you to participate in a dialogic experience with yourself in the same way I invited the audience at Hatfield. Notice where the words and concepts used here land inside you and the responses they invite. Notice when you tune out or dissociate, when you feel bored, or critical. You might notice a tightening in the chest or jaw, wanting to rubbish or pull away. You might feel a little tingle of excitement and connection, as if something touches you in the chest or heart that moves you, which allows you to remain open, as well as discerning.

Roots of compassion.

The word compassion has Latin roots: com (with) and pati, (suffering), i.e. “to suffer with”. Compassion is often seen as a fundamental core human quality and essential for healing. It lies at the heart of most religious traditions, and is present in many areas of secular life The actual active practice of compassion with which I am most familiar is from the Buddhist tradition, where it is an essential core practice. It originated two thousand years ago and has been studied ever since. A group of people in a contained environment practised over and over, again and again, and noted the outcomes of practice, discussing them and passing them on. The original findings of Gothama Buddha after his own six years of study brought us the fundamental understanding that is at the heart of Buddhist philosophy: the wish for all sentient beings to be free from suffering and its causes. Later came the understanding that suffering, once its roots were understood, could be overcome and ways offered to achieve this. The Buddhist practice of compassion lies within these teachings.

The Buddha’s brief instruction to the monks who were afraid to go into the forest was translated later by Buddhaghosa and included phrases such as ‘may all beings be happy’; ‘may all beings cultivate a boundless heart toward all sentient beings.’ This is known as metta, or loving kindness practice, and has been further developed for Western minds by many scholars including Sharon Salzberg in the US and Christina Feldman in the UK.

Just as CAT emphasises accurate description of reciprocal roles, shifting states and procedures - those patterns around suffering that tend to lead to things going wrong - so the philosophy around compassion insists on precision about what true compassion consists of. Compassion requires the mindful foundation of a firm base of body, feeling, thoughts and mind. Genuine compassion arises when we are touched inside. It is a sensory experience and there is a softening in the area of the belly and chest. We cannot offer compassion through just thinking about or over-identifying with another’s suffering. When we offer genuine compassion we join a person as we recognise their suffering, letting go of our fear and resistance and separateness to it. We do not resist emotional discomfort or harden down against it but fully accept it, opening into it with the wish to alleviate.

Self compassion

In loving kindness (metta) practice, the first instruction is to offer compassion to ourselves. We do this by imagining ourselves surrounded by all those people who have offered us kindness and love. We receive their kindness and love in gratitude. We then go on to offer compassion or loving kindness to family and friends, to people we meet as part of our everyday lives, to people we have difficulty with and then to all living beings. The important understanding here is that we need to nourish our own well of compassion and connect with the wider well formed by all who practise compassion, in order to offer it genuinely to others. This helps our well to grow deep and to weed out any self-centredness or ‘holier than thou’ attitudes.

Self-compassion is being integrated into many therapies. In The Mindful Path to Self-Compassion (2009), an excellent book, which I recommend to patients and colleagues, Harvard psychologist Christopher Germer suggests practical ways in which we may develop self-compassion, such as softening into the body; noticing and containing thoughts; befriending feelings and savouring our potential for spirituality. You can see that the basis for these practices is acceptance and unconditional friendliness. In the UK the Compassionate Mind Foundation developed by evolutionary psychologist Professor Paul Gilbert gives us the understanding that to promote compassion, which he suggests counteracts cruelty and indifference, we need a biopsychosocial approach. When the brain is in the mode of ‘self-protection’ its other potentials, including compassion, are less accessible. It is difficult to feel kind toward people we are very angry with, or have been hurt by, and this will include ourselves.

It may be inappropriate to offer compassion to patients who are still in reaction to trauma or abuse, for whom compassion can appear threatening. We need to understand our own, and others’, ‘fight/flight/freeze’ responses. We need to find and name the core pain behind the invitations to Merging/Merged or Admiring/Admired reciprocal roles before considering a compassionate statement toward this pain. We need to know whether we, or our patient, is likely to snag or sabotage anything seen as ‘good’ or helpful. And at the same time it is important to try to be kind!

Self-compassion is the main bedrock of compassion practice but it is hard for Westerners to offer compassion toward themselves. Compassion is often seen as selfish; indulgent; flakey; narcissistic; too soft or indecisive. Many of us have a well developed Critical Judging in relation to Criticised Judged self-to-self reciprocal role, or we value the rational, that which can be clearly accounted for - which means it’s hard to be open to accepting whatever feeling or sensation arises in the moment as a starting place, even if it is confusion, or not knowing, or feeling overwhelmed, and to find responses from there. Some therapists have also expressed concerns about collusion, or inflating an Admiring/Admired reciprocal role. These concerns are vital, for they invite us to be discerning about true and false compassion. Karen Armstrong writes, in Twelve Steps to a Compassionate Life, that whilst compassion is a natural aspect of our humanity, it has become alien to our modern world, with its individualistic and competitive economic system of capitalism, its many global and tribal wars and conflicts. And yet most of us understand, particularly when we see it in action through wise people such as Desmond Tutu, the Dalai Lama and Thich Nhat Hanh, that the practice of true compassion is inspiring, often helpful and sometimes transforming.

What helps us to build a capacity for true compassion is to cultivate Maitri – a Sanskrit word meaning ‘unconditional friendliness’ and loving kindness. This is essential for all mindfulness meditation and of particular importance for Western psyches used to developing reciprocal roles of Critical Judging in relation to Criticised and Judged with a core pain of hurt and worthless.

Christopher Germer suggests that we develop our own individual phrases that express self compassion around what we would like to change or nourish within ourselves. For CAT therapists this would be linking compassion with exits. For example:

- May I accept my difficult feelings (hurt, rage, worthlessness) without judging them.

- May my feelings have more space around them.

- May I find compassion for my difficult, often unbearable, feelings (hurt, rage.)

- May I notice and accept times when I am blaming, judging, critical or rubbishing to myself. (Later would be added ‘and to others’).

- May I find strength during this difficult time.

You can see that these offerings, based on compassion, are tailored to what the patient needs and can manage. They need to be realistic and they need to arise from genuine exchange. The “May I” of these practices is like drawing from the universal well of mindfulness energy and compassion. It is not limited. The more we practise and nourish it within ourselves and with others, the deeper the well becomes.

When our own well is nourished by the waters of compassion, we can offer it freely and easily, knowing that there are ways to replenish. It becomes a generosity that nourishes the giver and the receiver. In this way the practice becomes not individualistic or just for serving others because we are in the helping professions, but something universal. There is an important social construct here. We do not do it for outcome or wanting to feel good or be superior.

“Idiot compassion”

Some Buddhists have an interesting and harsh expression for compassion that is not true compassion. They call it ‘idiot compassion’. Paul Gilbert, who was also presenting at the Hatfield conference, suggested to me that this term should be avoided, as it is often misleading. But I quite like it because it sounds like a wake up bell, somewhat like those initiation sticks some Zen Masters use to keep their monks awake during the night sittings! When this phrase was offered to me by a true friend in response to something I was saying, I really took notice of it and have remembered it ever since. It reminds me to be discriminating. Its harshness also might help us avoid falling into the view that compassion is a soft option, which it is not. Whatever term we choose, the important thing is to make a distinction between true compassion and not genuine compassion. And here the difficulty and challenge begins, usually with each one of us having to really look deeply at our attitudes, without self- deception. Compassion which serves only the ego of the giver, or which helps to inflate an Admired/Admiring self in relation to a Rubbished/Rubbishing self is not true compassion; it’s an attempt to feel better, a kind of condescension. It can become patronising. There is an attachment here to the idea of compassion as something good or special. A possible split self-state might be: “either Idealised, Special and Holy, above and beyond base feeling or Despised, Needy and Ignorant”.

Compassion is more free to arise naturally when we have learned healthy separation, especially from being caught in reciprocal roles involving Merging in relation to Merged; Blessed in relation to bliss; Saviour or Rescuer in relation to Grateful Victim.

Compassion fatigue

Many of us experience this when we see yet more pictures in the news of starving children. We feel we have nothing left to give; we feel angry at our helplessness to do any more and at their helplessness in being in their predicament. If we have become exhausted by the demands of our jobs in environments where there is little support or appreciation, we may begin to notice a hardening down against any kind of suffering. Our own has become too much and there is no space for replenishing the well out of which we give. If we have become too attached to, or identified by, our role, too busy to think or feel, we may be too unaware of our own emotional suffering to open up, and then it will be very hard for us to feel into someone else’s core pain. True compassion asks us to be touched inside by the predicament of the people we see and just be alongside the other person as an equal, as the basically shaky person that we know we are, and the more we think we know, the less it feels we know. And to do this without losing sight of the task we have agreed to, in the chair marked ‘therapist’. Experimenting with loving kindness and compassion means of course coming straight up against our own reciprocal roles and procedures!

Compassion and CAT

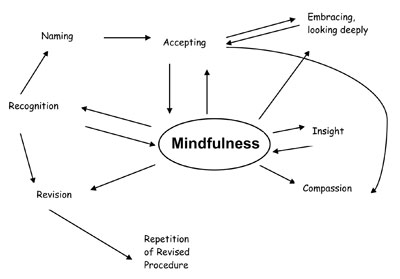

The recognition, accurate description and re-orchestration of self-states is one of the key activities of CAT in both complex and straightforward cases. CAT’s relational understanding in its model of reciprocity in role enactment means that the work of relating is ever present, even before meeting. Steve Potter in his 2004 paper, writes that he thinks of states as little knots of relational intelligence waiting to be loosened; that CAT is good at tracking damage to the capacity for self reflection and through the naming and accurate description of procedures offers a model of mindfulness.

It is this empowerment of our orchestrating, reflexive and assertive sense of self that brings us more dialogically into the inner and outer world and this increases the possibility for spaciousness and individual narrative.

From experiencing my enacted patterns as the person I am, as laid down by the power of early caregivers, I shift into experiencing these patterns as something I have learned to do habitually. And this step makes room for a space where self-reflection on what has been disallowed or dissociated from may arise. Where we begin an inner dialogue and relationship, an observer self is born who is able to see the multitude of states we call ‘me’. It’s this observer who is able to stand back from the domination of procedures and rigid reciprocal roles. In this space there’s the possibility of a dialogic overview. An understanding of where my suffering has been, what I do that continues my suffering, and what I do that releases this suffering, and thus allows me to consider healing and thus contemplate health, and wholeness, and even meaning. In this self-to-self dialogue I am more than the sum total of my difficulties, my diagnoses. I am a person engaged in a journey that includes suffering, and having problems. My freedom is in choosing my attitude, and being empowered to do this.

Our work in CAT is to actively encourage more spaciousness so that this Observer Self may grow more fully. There may be opportunities to find qualities within this Observer - free, wise, strong, knowing - Listening and Caring in relation to Listened to and Cared for. CAT gives permission and encouragement and the homework of repetition of aims means we are all having the opportunity to reframe the nervous system and encourage neuroplasticity, creating new neural pathways.

The process of CAT therapy including compassion might look something like this:

Self Compassion and the therapeutic relationship

If we are able to develop self-compassion through practising with the main metta practice, we have a chance of feeling freer from being caught in our own reciprocal roles and procedures, and thus freer to offer compassion toward our patients. In those moments when we meet the suffering of core pain in the room, our own and/or or the other person’s, without giving in to an immediate response or saying something because we do not know what else to say, the practice of compassion may be possible. When we are able to stand aside, not doing, but noticing being exquisitely touched by hurt, loss, rejection, and by helplessness, fear, aversion, rage, where our practice, in that moment, is to do absolutely nothing else than be there. We may be aware of the suffering in the room – and at the same time we may be aware of all other beings who have been and are being cruelly treated, marginalised, hurt, who have suffered loss or humiliation.

It’s my experience that out of these moments different words arise, and different CAT exits for the patient to practise between sessions. It’s possible for the simple ‘I am so sorry’ to arise which may transmit true compassion.

Sometimes the hidden or unformed parts of the patient are touched by the offering of genuine compassion, whether silent or spoken. These parts might then find the words to speak of their suffering.

Here are some suggestions for new reciprocal roles that could emerge from the practice of self compassion.

Reciprocal roles

- Listening to myself mindfully and compassionately in relation to being fully listened to and heard

- Holding my fragile self in the cradle of compassion in relation to being cradled in compassion

- Bathing my anxiety in the energy of mindfulness in relation to being mindfully present with what I feel

- Accepting myself just as I am, in whatever state, in relation to feeling accepted

- Giving kindness in relation to receiving kindness

- Open heart in relation to openly understood

Compassion within a CAT therapy

CAT is a very active therapy and completing the tasks in the required time frame can mean that we place less value of the quality of relationship unfolding. It’s my view that all of us come into this work with a kind heart or we would not be able to do it, so we are already practising a form of intention for kindness. We work flexibly with the patients’ own words and with what they can manage. We encourage experimenting, inviting playfulness where appropriate. We might work with the body, with metaphor, with pictures and dreams, but it is our presence that helps the revision of stuck patterns and painful procedures to feel safe and to loosen their hold. It is in the dialogue that emerges from this presence that healthy reciprocal roles might take root. And sometimes, for those encounters with patients who have been so damaged and brutalised it is barely possible for them to remain in the room with us, our silent and most mindful attention might be the only practice we both have.

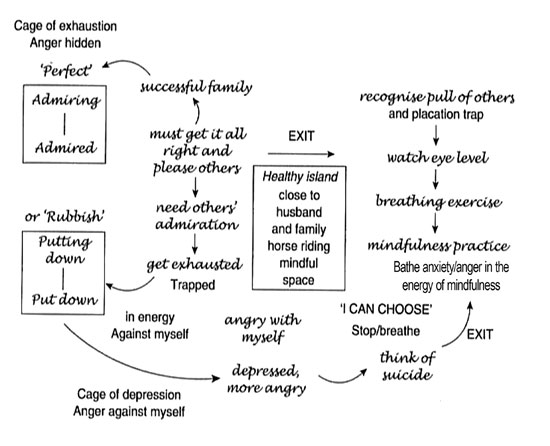

Here is a diagram for Amanda (see Change For The Better ed.3 Part 4) whose vulnerable and angry feelings had been firstly disallowed, then experienced as unbearable.

She had suffered from severe depression for many years and had been hospitalised, enduring many courses of ECT. She had had a CAT therapy several years earlier. After she returned to therapy and agreed to work with a Mindfulness based approach, we gradually added exits to her diagram based upon the outcome of her own mindfulness practice. With her permission I wrote about her in my article ‘Mindfulness within the practice of CAT’. When she found herself in the cage of her deepest depression she practised saying ‘May I be well; May I be free from suffering; May I be free from danger.’

Here is an example of the kind of homework we created together to help her to develop more compassion for her unbearable feelings. First we had to name accurately the different triggers that tended to lead to her falling into the ‘cage of depression’ and to self-harm and her homework was to develop awareness in the moment of each trigger

AWARENESS OF TRIGGERS TO MOVING INTO THE CAGE OF DEPRESSION AND HARMING MYSELF

- Vulnerability and helplessness due to maintaning constant vigilance for others’ acceptance

- Constant striving for idealised perfection

- Fear of my own angry and rageful feelings

- Rejection of all my difficult feelings

Next we developed manageable Exits

- Give space, through recognition and mindful breathing, for each of the triggers as it arises.

- Offer acceptance unconditionally to my:

- Vulnerability and helplessness

- Constant anxious striving

- Fear of rejection, my own and others’

- Fear and rejection of my angry feelings, toward myself and toward others

Then finally we moved into a third stage:

- Allow a softening of attitude toward my painful and difficult feelings

- Offer compassion to my difficult and painful feelings using the phrase: ‘May I find safety alongside you’ and ‘may I be well’ and ‘may I find healing’.

Patients with hidden or discrete states such as ‘little one’; ‘fragile self’; ‘the bud’, and states of feeling that have been disallowed or experienced as unbearable can find the offering of silent compassion gives an energetic space. After one such experience my patient Martha had a dream. “There was a hand, pale in the dark. It was a welcoming hand, open, like the hand in a Leonardo drawing. Not like my uncle’s fist! It remained there and I became curious. I found myself reaching out to touch it. Then I was holding hands and something broke open inside. I woke with tears on my face.”

There are many different ways to respond to this dream. In CAT terms this was the beginning of a new self-to-self reciprocal role of Noticing, Accepting safely in relation to Feeling Supported and Accepted.

Another patient, Leonie, practised with an exit she made using the phrase ‘May I accept my painful feelings just as they arise, without banishing them in shame’. Later she added, ‘May I bathe my painful feelings in kindness’ which emerged after she had experienced being ‘bathed in light’ when she walked in the woods, experiencing the ‘bathing’ as helpful and kind to her sore places. This became a powerful practice for her. It is possible to develop some short sentences for ourselves that helps us nourish our individual practice.

If we decide to practice self-compassion we must expect difficult feelings to arise – we should give them permission and not enter into combat as this hardens feelings down. We can experiment with accepting and offering compassion to our difficult feelings, even our most critical and rejecting ones. I think it’s important not to work too hard - the art is to allow all feeling and experience to be recognised, then touched by the process of naming the feeling we have recognised, and to stay only as long as is tolerable. Those of us with snags or self-sabotage procedures may also find it difficult to allow feelings such as ‘joy’ or ‘happiness’ without self recrimination or superstitiously thinking we will have to be punished or are inviting bad luck! We might also need to notice and touch the feeling or Self State of Harsh Judging in relation to Harshly Judged and Put down. This is allowing problematic reciprocal roles, core pain and procedures to come into our awareness, just as they are, without making them wrong or moving too quickly into action and change. This in itself often has a profound effect on patients, that their feelings, attitudes, behaviours, as they arise within the session are just there, not ignored or put down, not admired, judged or over-interpreted or rushed into exit, but just there, waiting to be seen and to begin the process of transformation.

In Buddhism, Nirvana is not some magical unreachable realm but something achieved in life through practising the four immeasurables: Maitri (loving kindness); Karuna (compassion – the wish to alleviate suffering); Mudita (sympathetic joy, taking delight in the happiness of others); and Upeksha or equanimity – loving and accepting all beings impartially and equally.

References

Armstrong, K., (2011). Twelve Steps to a compassionate life: Bodley Head.

Feldman, C., (2005). Compassion: Rodmell.

Germer, C., (2009). The mindful path to self compassion. Guildford.

Gilbert, P., (ed). (2005). Compassion. Conceptualisations, Research and Use in psychotherapy: Routledge, London and New York.

McCormick, E.Wilde, (2008). Change for the better: Sage.

Potter, S., (2004), Untying the knots: relational states of mind in Cognitive Analytic Therapy Reformulation article ACAT members website

Salzberg S. (2002) Shambhala Loving Kindness

Trugpa, C. (1987) Shambhala Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism

Elizabeth Wilde McCormick is a founder member of ACAT and has been in practice as a psychotherapist for over thirty years, both within the NHS and in private practice. She is the author of a number of self-help books including the CAT self-help book Change For The Better. The fourth edition of Change For The Better will be published in April 2012 with Sage and launched at the July ACAT conference.

Full Reference

Wilde McCormick, E., 2011. Compassion in CAT. Reformulation, Winter, pp.32-38.Search the Bibliography

Type in your search terms. If you want to search for results that match ALL of your keywords you can list them with commas between them; e.g., "borderline,adolescent", which will bring back results that have BOTH keywords mentioned in the title or author data.

Related Articles

CAT and CFT - Complementary in the treatment of shame?

Jameson, P., 2014. CAT and CFT - Complementary in the treatment of shame?. Reformulation, Winter, pp.37-40.

CAT in dialogue with Mindfulness: Thoughts on a theoretical and clinical integration

Jayne Finch, 2013. CAT in dialogue with Mindfulness: Thoughts on a theoretical and clinical integration. Reformulation, Winter, p.45,46,47,48.

Book Review: The Mindfulness Manifesto

Wilde McCormick, E., 2011. Book Review: The Mindfulness Manifesto. Reformulation, Summer, p.28.

Do We Allow CAT To Have A Heart - And If We Do, Does This Make It Soft And Wet?

McCormick, E., 1995. Do We Allow CAT To Have A Heart - And If We Do, Does This Make It Soft And Wet?. Reformulation, ACAT News Summer, p.x.

Letters to the Editors: Pausing for Breath, Personal Reflections on the War

Wilde McCormick, E., 2003. Letters to the Editors: Pausing for Breath, Personal Reflections on the War. Reformulation, Summer, pp.6-8.

Other Articles in the Same Issue

Aims and Scope of Reformulation

Lloyd, J., Ryle, A., Hepple, J. and Nehmad, A., 2011. Aims and Scope of Reformulation. Reformulation, Winter, p.64.

Black and White Thinking: Using CAT to think about Race in the Therapeutic Space

Brown, H. and Msebele, N., 2011. Black and White Thinking: Using CAT to think about Race in the Therapeutic Space. Reformulation, Winter, pp.58-62.

Book Review: "Why love matters – How affection shapes the baby’s brain" by Sue Gerhardt

Poggioli, M., 2011. Book Review: "Why love matters – How affection shapes the baby’s brain" by Sue Gerhardt. Reformulation, Winter, p.43.

CAT, Metaphor and Pictures

Turner, J., 2011. CAT, Metaphor and Pictures. Reformulation, Winter, pp.39-43.

Comment on James Turner’s article on Verbal and Pictorial Metaphor in CAT

Hughes, R., 2011. Comment on James Turner’s article on Verbal and Pictorial Metaphor in CAT. Reformulation, Winter, pp.24-25.

Compassion in CAT

Wilde McCormick, E., 2011. Compassion in CAT. Reformulation, Winter, pp.32-38.

Equality, Inequality and Reciprocal Roles

Toye, J., 2011. Equality, Inequality and Reciprocal Roles. Reformulation, Winter, pp.44-48.

Letter from the Chair of ACAT

Hepple, J., 2011. Letter from the Chair of ACAT. Reformulation, Winter, p.4.

Letter from the Editors

Lloyd, J., Ryle, A., Hepple, J. and Nehmad, A., 2011. Letter from the Editors. Reformulation, Winter, p.3.

Supervision Requirements across the Organisation

Jevon, M., 2011. Supervision Requirements across the Organisation. Reformulation, Winter, pp.62-63.

The Chicken and the Egg

Hepple, J., 2011. The Chicken and the Egg. Reformulation, Winter, p.19.

The Launch of a new Special Interest Group

Jenaway, Dr A., Sachar, A. and Mangwana, S., 2011. The Launch of a new Special Interest Group. Reformulation, Winter, p.57.

The PSQ Italian Standardisation

Fiorani, C. and Poggioli, M., 2011. The PSQ Italian Standardisation. Reformulation, Winter, pp.49-52.

The Reformulation '16 plus one' Interview

Yabsley, S., 2011. The Reformulation '16 plus one' Interview. Reformulation, Winter, p.67.

Using Cognitive Analytic Therapy for Medically Unexplained Symptoms – some theory and initial outcomes

Jenaway, Dr A., 2011. Using Cognitive Analytic Therapy for Medically Unexplained Symptoms – some theory and initial outcomes. Reformulation, Winter, pp.53-55.

What are the important ingredients of a CAT goodbye letter?

Turpin, C., Adu-White, D., Barnes, P., Chalmers-Woods, R., Delisser, C., Dudley, J. and Mesbahi, M., 2011. What are the important ingredients of a CAT goodbye letter?. Reformulation, Winter, pp.30-31.

Whose Reformulation is it Anyway?

Jenaway, Dr A., 2011. Whose Reformulation is it Anyway?. Reformulation, Winter, pp.26-29.

Working within the Zone of Proximal Development: Reflections of a developing CAT practitioner in learning disabilities

Frain, H., 2011. Working within the Zone of Proximal Development: Reflections of a developing CAT practitioner in learning disabilities. Reformulation, Winter, pp.6-9.

"They have behaviour, we have relationships?"

Greenhill, B., 2011. "They have behaviour, we have relationships?". Reformulation, Winter, pp.10-15.

Help

This site has recently been updated to be Mobile Friendly. We are working through the pages to check everything is working properly. If you spot a problem please email support@acat.me.uk and we'll look into it. Thank you.