Web-site restrictions

ACAT will be moving to a new web site on Thursday, 10th April.

In preparation, from Friday, 4th April this old web site will not let members renew their membership, and any other changes members make, e.g. their personal details, will get ‘lost in the move’.

Urgent membership renewals should instead be done by contacting Alison Marfell.

Working within the Zone of Proximal Development: Reflections of a developing CAT practitioner in learning disabilities

Frain, H., 2011. Working within the Zone of Proximal Development: Reflections of a developing CAT practitioner in learning disabilities. Reformulation, Winter, pp.6-9.

Introduction / outline

As a clinical psychologist working with people with learning disabilities I am conscious of the need to match therapeutic work to the level of ability of my client. This may be in terms of their cognitive abilities, what they are or are not able to understand at a verbal level, or their abilities to recognise and comprehend their emotions (and those of others). CAT emphasises the need to work within a client’s ‘zone of proximal development (ZPD)’ (Vygotsky, 1978) and provides a framework and tools with which to do so. In this paper I reflect on my first experience of using CAT as a trainee practitioner with a client with a learning disability and working within his ZPD (and my own).

The Zone of Proximal Development

Researching within the Soviet Union, Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) had a diverse range of interests and was a prolific writer prior to his death aged 37. His work in cognitive and child development has been particularly influential both within the fields of psychology and education. Vygotsky’s work highlights the social nature of learning, suggesting that a child does not learn in isolation, he does so in relation to others. How he comes to understand the world and himself is heavily influenced by his parents, teachers, peers and the society he lives in. This emphasis on the reciprocal and interactive nature of learning has been influential in CAT’s understanding of the development of the self, of target problem procedures and also the therapeutic relationship.

Vygotsky’s developmental research indicated that learning takes place in two stages, firstly through interaction with another, secondly by internalising the learning and being able to repeat it on one’s own. Vygotsky (1978, p86), suggested the zone of proximal development is

Working within the Zone of Proximal Development

“the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers”.

Scaffolding and the ZPD

Wood, Bruner, and Ross (1976) developed this further and introduced the concept of ‘scaffolding’. This refers to the support offered by the more knowledgeable other and also to the ‘tools’ that are offered to them in order to continue their own learning.

Leiman and Stiles (2001) have described how psychotherapy involves a developmental sequence of assimilation during which a therapist assists a client to begin to recognise, reformulate, understand and revise problematic experiences. They suggest that ZPD represents the “place where clients move through the continuum of assimilation with the therapists help”.

Within effective CAT therapists are mindful of the client’s ZPD. The strong emphasis on collaboration means that attempts to work beyond the client’s ZPD are quickly recognised either in therapy or in supervision as the dissonance within the therapeutic relationship often leads to a reciprocal role enactment; for instance, the client experiences the therapist as controlling and bullying, feels bullied and submissive and withdraws into silence or doesn’t complete homework tasks.

Assessing Alex

Alex was referred by a consultant psychiatrist. He has Prada Willi Syndrome, which in his case has led to learning disabilities and hyperphagia – difficulties with controlling appetite. In some individuals it can lead to arrested sexual development. Alex lives in a specialist residential home for people with PWS where he is on a strict calorie controlled diet and access to the kitchen is restricted. During our initial assessment Alex described not feeling like a “real man” and connected this mainly to penis size (which was assessed by his G P as within the normal range) but he also described a pervading controlling to controlled reciprocal role.

I used an adapted version of the psychotherapy file with Alex. It did not particularly add anything new in terms of reformulatory material but it did provide a useful insight into Alex’s receptive language abilities and understanding. This aided my ability to ensure my language in sessions and the reformulation material remained in his Zone of Proximal Development.

The assessment phase gave me the opportunity to familiarise Alex with the CAT tools e.g. diagrams, by making them a part of the way we worked. I drew out the controlling to controlling role very early on, supplemented with stick figures to represent the concepts. Initially the controlling role focused on his family who had always told him what to do and had, during his childhood been physically abusive.

Reformulating in Alex’s ZPD

Reformulation letter

Using the client’s language the therapist begins to provide descriptions of difficult states or procedures and these are internalised and later used by the client in order to describe and understand their difficulties. Such understandings are deepened by the reformulation letter which provides a shared understanding of the development and maintenance of difficulties and outlines an agreed agenda for the continuing therapy. A standard prose reformulation letter was clearly not going to facilitate work within Alex’s ZPD. With encouragement from my supervision group I developed a booklet with one concept per page, using some of the existing prose, with a picture or diagram on the opposite page that captured the key concept. The booklet contained the following aspects;

- Why Alex had engaged in therapy,

- The development of his difficulties,

- Continuing problems, namely feeling controlled or pampered by his family, his condition and sometimes staff and getting too close to people and getting hurt,

- How we might work in therapy and how it might help.

The booklet described TPP’s as patterns, “what I think, what I feel and what I do” and described the following;

-

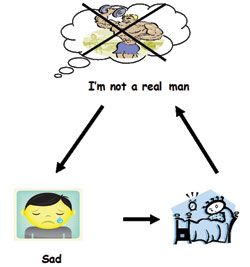

Letting my thoughts get me down

Letting my thoughts get me down

I worry that my penis is too small. I think I am not a ‘real man’. This makes me low. I stay in my room not feeling any better and feel bad about myself. I carry on worrying that my penis is too small.

-

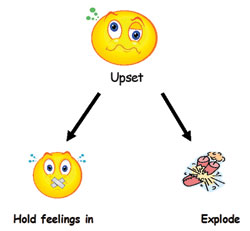

Holding my feelings in

Holding my feelings in

Either I hold my feelings in and don’t get the things I want or I explode and hurt people which causes trouble and makes me feel bad.

-

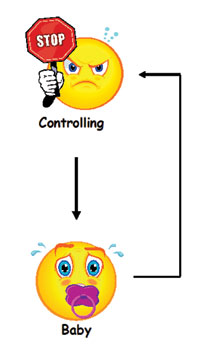

Feeling controlled

Feeling controlled

Other people often tell me what to do. I give in and do as they say but feel I am missing out. They are controlling me and make me feel like a baby. Other people don’t learn that I can make my own choices. They keep telling me what to do.

Sequential Diagrammatic Reformulation

The second aspect of reformulation, the Sequential Diagrammatic Reformulation (SDR), provides a semiotic shorthand for both client and therapist to describe and explore repeating patterns of behaviours and states. It becomes in itself a sign between therapist and client, with shared meaning for the client’s experiences, for instance they may begin to discuss the ‘green loop’ rather than the experience of social avoidance as a result of a critical to criticized reciprocal role. The SDR can be developed at the client’s pace, perhaps starting with a single state.

When Alex was familiar with the concepts in the reformulation booklet I brought to our session print outs of all the illustrative diagrams and pictures used in the reformulation booklet, two pairs of scissors, glue and a large sheet of paper with which to construct the SDR. Having explained what we were going to do I suggested we needed a starting point. Alex and I had just talked about difficulties with his parents on a recent home visit and he felt that ‘doing controlling’ was a very important issue. He cut out what had become the ‘controlling to baby’ role and stuck in on the paper. Over the next two sessions we continued to map out how feeling like a baby made him feel either sad or angry and the procedures that ensued.

I am aware that the cutting and sticking might seem a little ‘Blue Peter’, but I feel it was effective in three ways;

- The pictures helped us develop a shared language, Alex could point to a picture on the map and say “I felt a bit ___” and I would understand what he meant.

- It made the process of developing the SDR quite relaxed, neither of us felt under pressure to produce a perfect diagram and we were able to discuss his experiences as we constructed it.

- It provided a useful way to keep the ‘controlling to controlled / baby’ role within our relationship in check. If I felt myself reaching for the scissors before we had agreed something I would pull back or occasionally Alex would tell me to “hold up” and we would discuss it further and agree who would do the cutting and sticking.

Whilst we identified more than one reciprocal role, Alex felt this one as the most important to him. It impacted on his feelings about himself as a “real man” and captured his relationships with his family, staff and peers. In order to remain within his ZPD and not overwhelm him with too many concepts we agreed to make the controlling to controlled role the main focus of the SDR and our subsequent work.

Recognition and Revision within Alex’s ZPD

Alex made good use of simple diaries that used the diagrams from the SDR. He was increasingly able to recognise the controlling to controlled role when enacted by others. A harder task was helping him consider when he might be in the controlling role. Through discussion he was able to recognise that certain behaviours from him led to certain responses in others, for instance if he procrastinated before going out staff would ask him if he was nearly ready, which he perceived as nagging. He was not able to consider self to other or self to self reciprocation any further.

Alex saw the controlling to controlled role being enacted frequently in his parents responses to him smoking, however he also decided that he was not ready to discuss this with them and decided to focus on making changes in his relationships with staff. Alex and I began to develop a booklet that would help staff support him to make some changes and also suggest changes that they could consider in order to help him. We used the diagrams from the reformulation booklet to think about changes Alex could make to help him and staff exit from the controlling pattern. For instance, being ready for appointments on time so staff wouldn’t have to ‘nag’. We then jointly discussed the booklet at a workshop for staff.

Ending

The second booklet we developed and shared with staff contained details of the patterns we had recognised, worked on and next steps, and as such formed part of what might normally be contained within a goodbye letter. I produced a second shorter letter that focused on our relationship. Within this I was keen to remind him how hard he had worked and also highlight the differences between our relationship and those he had with some members of staff. Alex, having been prepared over several weeks, had also produced a good bye letter, based on some heading suggestions I had given him. At the final session Alex described feeling more in control and ‘like a real man’.

Conclusions

For Alex there were potentially physical factors that were impacting on his relationship to his body and ultimately his self of being a “real man”. Whilst reassurance was given by the G P with regards to the size of his penis, Prada Willi Syndrome can impact on function and testosterone levels. Alex’s relationship with his body was an area that could have been given more emphasis within therapy, perhaps the minimal attention I paid to the issue reflects the limitations of my own ZPD at the time.

Working within a client’s ZPD is essential no matter what the client group. Given Alex’s learning disability extra consideration needs to be given to his abilities to understand and process verbal and emotional information.

I feel that four key factors helped me to work within Alex’s ZPD and make the work helpful for him;

- Creating a validating therapeutic environment that acknowledged the importance of Alex’s concerns as he had not experienced this before. Possibly for the first time we labelled his difficult experiences and emotions which legitimised his concerns and gave him a way to talk about them.

- Consistency – Using his words as far as possible we used the same phrases and expressions to describe his experiences and CAT concepts throughout our work. Again we used the same pictorial symbols throughout the work and these developed a strong shared meaning. Alex could describe a reciprocal role and target problem procedure simply by pointing to a series of pictures.

- Providing clear and structured homework between sessions. Alex kept a diary of when he experienced one end of the key reciprocal role and was consistently able to recognise these.

- Inviting his key worker in at the end of the session in order to share aspects of our work that Alex wanted them to know about. This meant that they developed their understanding of him and were able to help him use the tools, e.g. the SDR and the diaries therefore aiding his consolidation and between session learning.

Contact Details

Dr Helen Frain, Clinical Psychologist

Department of Learning Disabilities

Highbury Hospital, Highbury Rd, Nottingham NG6 9DR

Email: helen.frain@nottshc.nhs.uk

References

Leiman, M. & Stiles, W. B. (2001). Dialogical Sequence Analysis and the Zone of Proximal Development as conceptual enhancements to the assimilation model; The case of Jan revisited. Psychotherapy Research, 11 311-330.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind and society: The development of higher psychological processes. (p86). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wood, D., Bruner, J., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 17, 89-100.

Bibliography

Baum, S. & Lynggaard, H. (Eds) (2006). Intellectual Disabilities: a Systemic Approach. London: Karnac.

Beail, N. (2003). What works for people with mental retardation? Critical commentary on cognitive-behavioural and psychodynamic psychotherapy research. Mental Retardation, 41: 468-472.

Collins, S. (2006). “Don’t dis me!” Using CAT with young people who have physical and learning disabilities. Reformulation, Winter. 13-18.

David, C.(2009). CAT and people with learning disability: Using CAT with a 17 year old girl with disability. Reformulation, Spring. 8-14.

King, R. (2000). CAT and learning disability. Association of Cognitive Analytic Therapy News, Spring, 3-4.

Psailia, C.L. & Crowley, V. (2006). Cognitive Analytic Therapy in people with learning disabilities: AN investigation into the common reciprocal roles found within this client group. Mental Health and Learning Disabilities: Research and Practice, 2 (2), 96-108.

Professional Affairs Board of the British Psychological Society (2000). Learning Disability: Definitions and Context. British Psychological Society.

Leiman, M. (1992). The concept of the sign in the work of Vygotsky, Winnicott and Bakhtin: Further integration of object relations theory and activity theory. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 65, 209-221.

Lievegoed, R. (2006). Treating people with intellectual disabilities who are traumatized with EMDR. Poster presented at the European conference of the International Association for the Scientific Study of Intellectual Disability, Maastricht, 2-5 August 2006.

Ryle, A. & Leiman, M. (1990). La terapia analitico-cognitiva: Un approccio intergrativo. In Mancini, F & Semerari, A. (Eds) Le teorie cognitive dei disturbi emotive. La Nuova Italia Scientifica.

Ryle, A. & Kerr, I. B. (2002) Introducing Cognitive Analytic Therapy: Principles and Practice. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Stiles, W.B., Elliot, R., Llewelyn, S.P, Firths Cozen, J.A., Margison, F.R., Shapiro, D.A., & Hardy, G. (1990). Assimilation of problematic experiences by clients in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 27, 411-420.

Stiles, W.B., Morrison, L.A., Haw, S.K., Harper, H., Shapiro, D.A., S.P & Firths Cozen, J.A. (1991). Assimilation of problematic experiences by clients in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 28, 195-206.

Verhoeven, M. (2006). A life worth living: borderline personality and intellectual disability: dialectical behaviour therapy. Paper presented at the European conference of the International Association for the Scientific Study of Intellectual Disability, Maastricht, 2-5 August 2006.

Wells, S. (2009). A Qualitative Study of Cognitive Analytic Therapy as Experienced by Clients with Learning Disabilities. Reformulation, Winter, 22-23.

Full Reference

Frain, H., 2011. Working within the Zone of Proximal Development: Reflections of a developing CAT practitioner in learning disabilities. Reformulation, Winter, pp.6-9.Search the Bibliography

Type in your search terms. If you want to search for results that match ALL of your keywords you can list them with commas between them; e.g., "borderline,adolescent", which will bring back results that have BOTH keywords mentioned in the title or author data.

Related Articles

Musings on Doing CAT with Couples

Gray, M., 2006. Musings on Doing CAT with Couples. Reformulation, Winter, pp.29-31.

Psycho-Social Checklist

-, 2004. Psycho-Social Checklist. Reformulation, Autumn, p.28.

Helping service users understand and manage the risk: Are we part of the problem?

Crowther, S., 2014. Helping service users understand and manage the risk: Are we part of the problem?. Reformulation, Winter, pp.41-44.

A Qualitative Study of Cognitive Analytic Therapy as Experienced by Clients with Learning Disabilities

Wells, S., 2009. A Qualitative Study of Cognitive Analytic Therapy as Experienced by Clients with Learning Disabilities. Reformulation, Winter, pp.21-23.

A first experience of using Cognitive Analytic Therapy with a person with a learning disabilit

Westwood, S., & Lloyd, J., 2014. A first experience of using Cognitive Analytic Therapy with a person with a learning disabilit. Reformulation, Summer, pp.47-50.

Other Articles in the Same Issue

Aims and Scope of Reformulation

Lloyd, J., Ryle, A., Hepple, J. and Nehmad, A., 2011. Aims and Scope of Reformulation. Reformulation, Winter, p.64.

Black and White Thinking: Using CAT to think about Race in the Therapeutic Space

Brown, H. and Msebele, N., 2011. Black and White Thinking: Using CAT to think about Race in the Therapeutic Space. Reformulation, Winter, pp.58-62.

Book Review: "Why love matters – How affection shapes the baby’s brain" by Sue Gerhardt

Poggioli, M., 2011. Book Review: "Why love matters – How affection shapes the baby’s brain" by Sue Gerhardt. Reformulation, Winter, p.43.

CAT, Metaphor and Pictures

Turner, J., 2011. CAT, Metaphor and Pictures. Reformulation, Winter, pp.39-43.

Comment on James Turner’s article on Verbal and Pictorial Metaphor in CAT

Hughes, R., 2011. Comment on James Turner’s article on Verbal and Pictorial Metaphor in CAT. Reformulation, Winter, pp.24-25.

Compassion in CAT

Wilde McCormick, E., 2011. Compassion in CAT. Reformulation, Winter, pp.32-38.

Equality, Inequality and Reciprocal Roles

Toye, J., 2011. Equality, Inequality and Reciprocal Roles. Reformulation, Winter, pp.44-48.

Letter from the Chair of ACAT

Hepple, J., 2011. Letter from the Chair of ACAT. Reformulation, Winter, p.4.

Letter from the Editors

Lloyd, J., Ryle, A., Hepple, J. and Nehmad, A., 2011. Letter from the Editors. Reformulation, Winter, p.3.

Supervision Requirements across the Organisation

Jevon, M., 2011. Supervision Requirements across the Organisation. Reformulation, Winter, pp.62-63.

The Chicken and the Egg

Hepple, J., 2011. The Chicken and the Egg. Reformulation, Winter, p.19.

The Launch of a new Special Interest Group

Jenaway, Dr A., Sachar, A. and Mangwana, S., 2011. The Launch of a new Special Interest Group. Reformulation, Winter, p.57.

The PSQ Italian Standardisation

Fiorani, C. and Poggioli, M., 2011. The PSQ Italian Standardisation. Reformulation, Winter, pp.49-52.

The Reformulation '16 plus one' Interview

Yabsley, S., 2011. The Reformulation '16 plus one' Interview. Reformulation, Winter, p.67.

Using Cognitive Analytic Therapy for Medically Unexplained Symptoms – some theory and initial outcomes

Jenaway, Dr A., 2011. Using Cognitive Analytic Therapy for Medically Unexplained Symptoms – some theory and initial outcomes. Reformulation, Winter, pp.53-55.

What are the important ingredients of a CAT goodbye letter?

Turpin, C., Adu-White, D., Barnes, P., Chalmers-Woods, R., Delisser, C., Dudley, J. and Mesbahi, M., 2011. What are the important ingredients of a CAT goodbye letter?. Reformulation, Winter, pp.30-31.

Whose Reformulation is it Anyway?

Jenaway, Dr A., 2011. Whose Reformulation is it Anyway?. Reformulation, Winter, pp.26-29.

Working within the Zone of Proximal Development: Reflections of a developing CAT practitioner in learning disabilities

Frain, H., 2011. Working within the Zone of Proximal Development: Reflections of a developing CAT practitioner in learning disabilities. Reformulation, Winter, pp.6-9.

"They have behaviour, we have relationships?"

Greenhill, B., 2011. "They have behaviour, we have relationships?". Reformulation, Winter, pp.10-15.

Help

This site has recently been updated to be Mobile Friendly. We are working through the pages to check everything is working properly. If you spot a problem please email support@acat.me.uk and we'll look into it. Thank you.